Nobody knows precisely what was uttered at Sinai; our Sages and scholars over the generations have offered numerous hypotheses: beginning with the notion that condenses the revelation to the single Hebrew letter of Alef - the first letter of the Ten Commandments as well as denoting the very core of the Holy Tongue and all its roots – through the assertion that only the first two Commandments were spoken at Sinai, or that all Ten Commandments were actually uttered; and culminating in the belief that claims that the entire Torah and Mishna, including all the interpretations and commentaries that were ever written, as well as all those yet to be written – all, without any exception, are embedded within the verses of the Torah and were thus given at Sinai.

Every year we celebrate Chag Matan Torah, the festival of the giving of the Torah. However, one might say that each and every Israelite received a different facet of the Torah, and that each individual was bestowed a unique angle of the Divine Revelation. The days in which we find ourselves now, like other special days in the Jewish calendar, invoke and elicit an abundance of Torah teachings, novel ideas, new commentaries and innovative interpretations – all of which have already been given at Sinai, even though no human ear has yet heard them. It is described thus: when we come and offer an avant-garde commentary on Torah words, Moshe inquires with some surprise as to the source of the new interpretation, to which God Himself replies that the newly-suggested commentary had already been told to Moshe at Sinai, but was forgotten or misunderstood or lost somewhere in the midst of the intricacies of the implicit words and phrases, and has now been retrieved and recalled by ourselves.

In this light - what then was given to us at Sinai? The explicit or the implicit? The existing or the void? One single letter or the entire Torah? Or perhaps one letter containing all words and all commentaries ad infinitum? It probably doesn't really matter, because Jews were never wary of saying that the words of the Mishna and the entire exegesis on the Torah were written by human beings and are not Divine texts (as the Ktzot HaChoshen himself says in the introduction to his book bearing the same name), and they were still considered God-fearing and observant Jews; and on the opposite end, we can find those who stood at Mt. Sinai and saw the sounds with their own eyes, and very soon after were able to sin, go astray and exhibit ingratitude for all they had just received.

Following are three things that were undoubtedly given at Sinai:

The first is that all must feel humbled before the Divine Infinity. The Divine Revelation and the giving of the Torah annulled all forms of human dictatorship, and called for the freedom of Man, leaving room for the rule of God alone; they also gave validity to those hesitant, humble commentaries, and turned assertive lawmakers into commentators of equal standing. Humility and modesty were demanded of great scholars and simple folk alike, not as opponents, but as equals standing before the same authority. Some narrow-minded people may see this as anarchy, but we view it as freedom; some take this to be a form of nihilism, yet we see it as an opportunity for wisdom and knowledge.

The second thing given to us at Sinai was the notion that nobody is alone in this world - an idea quite novel at a time when gods were perceived as indifferent to human beings and their wars. At Sinai, there appeared a God that was benevolent and wished for His people to live and to prosper without demanding of them lip service, human sacrifices or suffering; a God before whom all were equal, men and women, strangers and Jews. You are standing this day all of you before Me, your women and your young and all those living with you, even the strangers among you. We all saw the Divine fire and so it belongs to no one exclusively. We are all loved and embraced, but only when united - from the woodchopper among us to the man who draws water from the well.

The third thing given at Sinai was the concept of the mundane and the unsacred. In the pagan world all things were sacred, everything was controlled by one god or other; control was taken out of the hands of people and placed in those of the gods, and people turned into victims of the gods, dictators, fools and perverts. In the pagan world there were leaders who pretended to talk in the name of a god that demanded nothing short of everything - one's body, one's soul, one's possessions – and people followed them blindly. At Sinai, the concept of sanctity was concentrated and compressed, and the world was taken from the gods, who had held it captive, and given back to all of us. Private possessions, the right to education, the division of lands and their redemption, the right over one's physical body – all these were restored to people by the Torah, along with the freedom to act and rectify within a world that, perhaps for the first time in the history of humankind, suddenly had an element of the mundane, a realm of things unsacred. The novel concept was not that heavens belong to God, but that the earth belongs to Man.

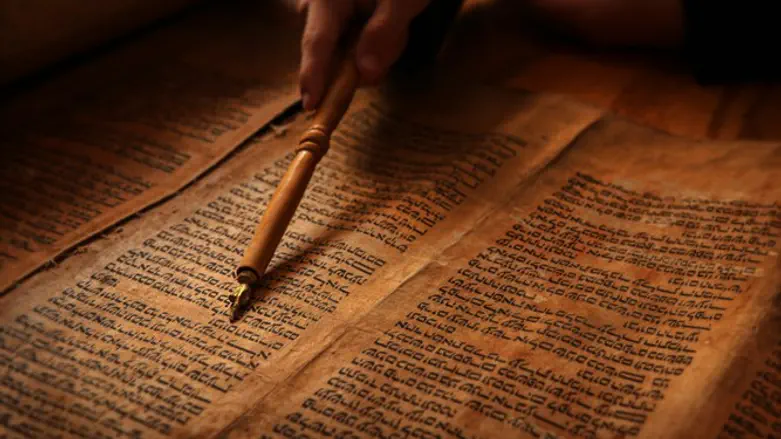

And every exegesis and every word of Torah stem from the insight that there is both compassion and justice; there is freedom but there are also obligations and commandments. So perhaps this is what was given at Sinai, and we have simply forgotten to listen to the white fire, and instead give precedence to the black fire written upon it in ink.

Rabbi Shlomo Vilk is Rosh Yeshiva of the Robert M. Beren Machanaim Hesder Yeshiva